The Innovative Media Research and Extension team presented on this topic at the 2021 ACE Conference (Association for Communication Excellence – June 23, 2021). We shared our approach on how we prioritize accessibility when we design educational media such as learning games, apps, and virtual labs.

We are all on a spectrum of need

Accessibility isn’t just for a set group of users: it is something that all users need. Accessibility represents a set of product characteristics that relate to service, environment, and system (such as game or website). Accessibility is about user needs, and accessible features must be actively designed. All users fall somewhere on a continuum of need (permanent, temporary, situational): any given user’s vision may range from good to poor or include issues with contrast or color; their hearing range could vary or they may use the media in a location where they are unable to enable sound; their cognitive skills may be different from those the media was primarily designed for; and their motor skills may cause them to seek ways to remap their interactions with the virtual and physical interface.

Design teams can make digital media better for all users by addressing accessibility demands, enabling as many people as possible – with the widest range of needs – to access and use their products. The social model of disability (Oliver, 2013) defines disability as a mismatch between the design and the person's needs, instead of as a personal health condition. This model reminds us that the challenge isn’t on the shoulders of the users: accessible design is the responsibility of the designers. Bad design disables people, and good design enables people (Figure 1).

Our process for accessibility

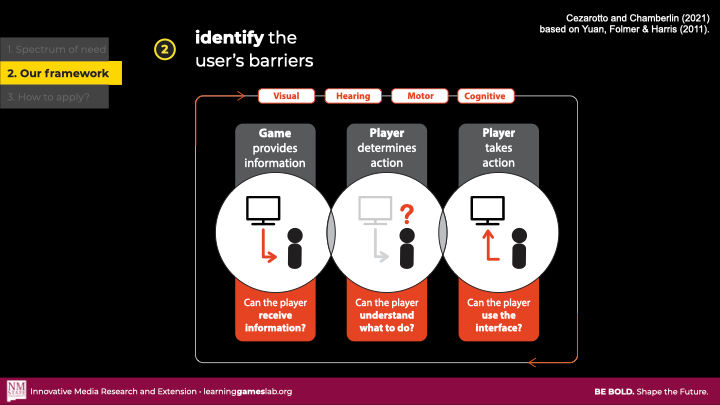

Researchers and developers on the Innovative Media Research and Extension team approach design as a process: accessibility is one part of this process, which they seek to constantly improve. With more than 40 years designing educational media, the team has always looked for ways to increase accessibility. Over time, the team has articulated a research-based accessibility framework to better address user needs. The framework seeks to (Figure 2):

Provide an overview picture of the main types of disabilities: The four main categories of disabilities – visual, hearing, motor, cognitive, motor (Gilbert, 2019; Aguado-Delgado et al., 2018; Yuan, Folmer & Harris, 2011; Bierre et al., 2004) – offer a lens to facilitate discussion, provide an overview picture of disabilities and allow the identification of possible barriers players may face in games.

Identify the user’s barriers faced in the media interaction cycle: Design teams can identify possible barriers users may face in media interaction. The interaction between users and the tool they are using happens in a cycle: the users Receive Stimuli from the system (visual, auditory, tactile stimuli), after which they Determine Responses (cognitive decision-making), which allows them to Provide Input (take action through the physical and virtual media interface) (Yuan, Folmer & Harris, 2011). Based on the established types of disability and this interactive cycle, there are three key questions to ask about a product (Cezarotto and Chamberlin, in press):

Can the user receive information?

Can the user understand what to do?

Can the user use the interface?

3. Recognize the existence of a large range of user needs and variability: Disabilities

don’t exist in discrete boxes: they are often co-diagnosed, with any given user having

needs across several different types of issues. Additionally, each area of need exists

within a spectrum, from low to high, can be co-diagnosed and may have specific types

within each category - for instance, on visual needs, a legal blind user will have different

needs from a user with low vision or with color blindness.

How can you approach accessibility on your team?

There is not one single way to approach accessibility. Many things can impact teams' different processes and decisions. Our framework may help your team to establish your own process. Here is what works for us (Figure 3):

Engage the entire team: make accessibility everyone’s priority, establishing goals and reviewing old products. Identify what works and discuss with your team, taking into consideration your possibilities and constraints.

Get knowledge on accessibility: look for external knowledge from accessibility experts, other studios, reviewing the literature, and participating in conferences and training.

Make it a recurring process: create a document that the team can easily access and update, and assume guidelines need to be constantly revised based on learning from projects, interaction with other studios, consultation with accessibility experts, or technological advancements.

Reference

Aguado-Delgado, J., Gutiérrez-Martínez, J. M., Hilera, J. R., de-Marcos, L., & Otón, S. (2018). Accessibility in video games: a systematic review. Universal Access in the Information Society, 1-25.

Bierre, K., Hinn, M., Martin, T., McIntosh, M., Snider, T., Stone, K., & Westin, T. (2004). Accessibility in games: Motivations and approaches. White paper, International Game Developers Association (IGDA).

Cezarotto, M. A, Chamberlin, B. A. (in press) Towards accessibility in educational games: a framework for the design team. InfoDesign - Brazilian Journal of Information Design.

Gilbert, R. M. (2019). Inclusive Design for a Digital World: Designing with Accessibility in Mind. United States: Apress. doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-5016-7

Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & society, 28(7), 1024-1026. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

Yuan, B., Folmer, E., & Harris, F. C. (2011). Game accessibility: a survey. Universal Access in the Information Society, 10(1), 81-100. doi: 10.1007/s10209-010-0189-5

To learn more about our products and design process contact:

Barbara Chamberlin, PhD

Interim Department Head

Extension Educational Media Specialist

bchamber@nmsu.edu

575-646-2848

Post written by: Matheus Cezarotto, PhD, Post Doctoral Researcher, matheus@nmsu.edu